The Other Side of Math

∞ PART EIGHT ∞

DOES A TEACHER NEED THE

SCHOOL BOARD’S APPROVAL

BEFORE USING PROBLEM CREATION?

DOES A TEACHER NEED THE SCHOOL BOARD’S APPROVAL BEFORE USING PROBLEM CREATION?

DOES A TEACHER NEED THE SCHOOL BOARD’S APPROVAL BEFORE USING PROBLEM CREATION?

The above question implies two additional but more general questions:

Question One: Does a teacher – any teacher of any subject – have the right, the duty and the mission to encourage and assist her students to generate and develop their own ideas about the subject they are studying, or should the teacher, intentionally or unintentionally, work to restrict her students to that limited set of personal opinions, fundamental beliefs and “truths” stated by the author(s) of that textbook or given by the teachers themselves?

Question Two: Should we assist our students to think for themselves or do we want and require them to hold in their minds and communicate to others much the same ideas we consider to be right and true?

In 21st Century America, neither of these questions makes much sense. As a group, Americans have decided long ago in favor of independent thought. We, fortunate inheritors of the most powerful tradition of freedom of thought and expression this world has seen, have the right to think our own ideas and express them to others.

But there will be people reading this paper on The Other Side of Math who live not in the United States of America (or in countries with similar degrees of freedom of thought and expression) but under governments and systems whose laws, authorities and rulers specifically prohibit such freedom. These governments and their rulers are so convinced of the rightness of their own ideas and actions that they require everyone in their domain to hold and communicate the same ideas and opinions they have – sometimes under penalty of fine, imprisonment or death for holding and/or expressing other ideas.

Obviously, this paper on OSOM is not for people who are afraid of human beings gaining possession of their own independent ideas.

And that observation brings me back to my original question:

DOES A TEACHER NEED THE SCHOOL BOARD’S APPROVAL BEFORE USING PROBLEM CREATION?

Let’s consider the tradition of Science Fairs: Why do primary and secondary schools hold annual Science Fairs?

So that all the participants can execute the same experiments from the same reference books? Don’t we harbor the hope that, eventually, after some years of participating in Science Fairs, at least some of those young people – the best of the bunch – will reach scientific escape velocity and extrapolate beyond the standard experiments described in their books to create something new and wonderful and useful?

Earlier today (August 2, 2016) in preparation for my school’s new school year (which starts August 8th), I was reviewing our first grade writing curriculum. I came across an activity to be done by all first graders towards the end of their first grade year, after they have mastered some writing basics like good penmanship, what is a noun, what is a verb, what is a sentence, what is an article, question marks, exclamation points, etc. This activity’s title is:

“Creative Sentences”

And that’s exactly what our 6-year-old boys and girls are expected to do – create sentences. “Creative Sentences” marks the formal beginning of the creative process in our writing program. No longer are the kids merely practicing good penmanship. No longer are they merely copying lists of nouns, action verbs and “The black cat runs.” Now they must write their own sentences using their own words.

If, with their book firmly closed, from their own mind and memory, their created sentence is just “A red fish jumps” (and that sentence was not one they had already copied from their book), they are now actually and for real on their way up the tall, tall ladder that one happy day leads to their first novel.

This might sound terribly elementary, but it is not elementary to the kids or teachers. Both members of that classroom team are working hard: the teacher to encourage “creative sentences” and the child to actually write “creative sentences”. The teacher knows that this simple activity elevates the individual from skilled parrot to creative writer.

Let’s return to the first grade classroom. Writing time is over. What’s next on the schedule?

MATH TIME IN FIRST GRADE!

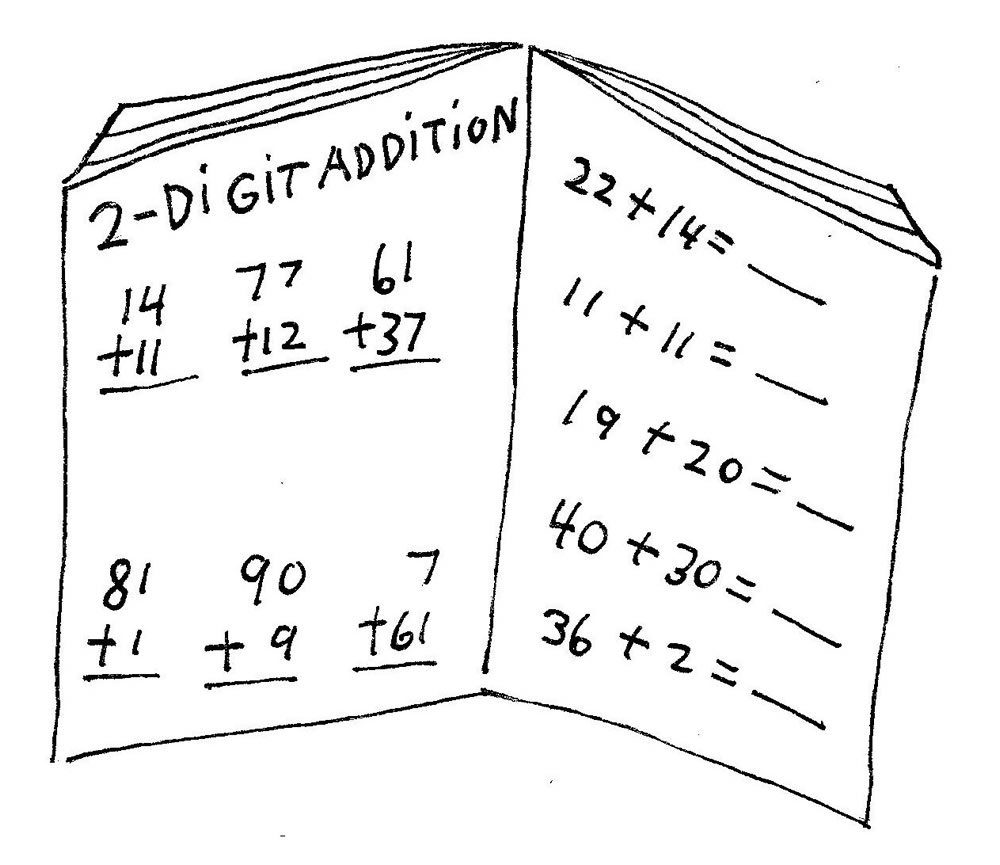

When it’s math time in your school, do your students master the book’s unit on 2-digit addition….

…and then take that next step where they create and solve 2-digit addition problems of their own?

Or, are they directed as usual to the next new math unit where they learn about an entirely different topic, like 2-digit subtraction? Or shapes? Or measuring?

And if they are not encouraged to create their own 2-digit addition problems, why? Wouldn’t a slightly more creative mathematician be a better product from their math time? Why not take a small but creative step forward and enhance the student’s independent ability to create with mathematics on his own? Even if this only means that he somehow manage from his very own mind and memory (with his textbook firmly closed) to pencil a single two-digit addition problem on a blank page — a problem that was not copied from his math book?

13 + 25 = ___

And then, when the student’s new numbers are on the paper, can he sketch what the 13 and the 25 represent? 13 what? 25 what? Are they plastic soldiers from his army of plastic soldiers at home?

What if the student were then encouraged to tell a brief story about why the 13 was being added to the 25? Did Christmas bring 25 more soldiers to the 13 he already had?

And what if he had to write a few more of his very own 2-digit addition problems, until writing them was easy?

And then solve his own problems and check his answers all by himself until solving and checking his own problems was easy?

MATH TIME IN THIRD GRADE!

Soon after studying this “Creative Sentences” material in our first grade curriculum, I re-read a description of our third grade reading program. Our 8-year-olds read lots and lots of books. After completing each book, they write a short essay about the story. They are provided with a list of five suggestions. The last one is my favorite!

5) “Write down how you could improve the story. You could give it a new ending or make it more exciting, etc.”

This suggestion is a bold invitation to create new ideas based upon existing data.

To carry out this suggestion, the third graders must create something that did not exist a moment before: new ideas — their own new ideas.

Following that mental creation, they must somehow get those ideas out of their heads onto paper in a readable form.

Well, look what happens if I simply aim the above writing suggestion directly at mathematics.

Question: “How could you improve the story of mathematics?”

“How could you improve the way the book teaches you to add (subtract, multiply or divide)?”

Question: “How could you give math a new ending?”

“How could you contribute new knowledge, methods or applications to the subject of mathematics?

Question: “How could you make math more exciting?

Question: “Could you develop a method that makes math more interesting?

While I believe my questions represent worthwhile goals, they are obviously far, far too much for third grade.

But the following exercise is not too much. IN FACT I DO IT ALL THE TIME:

What if, after they have mastered, for example, a set of new math skills like understanding the place values of greater numbers (thousands, tens of thousands, and hundreds of thousands) and successfully completed the book’s exercises on that topic, how about then, at that moment, before they are directed forwards in the text to begin the next new topic, they are told:

- To write their own greater numbers without referring to their teacher or book?

- To make their greater numbers different from the book’s numbers?

- To continue to write their own large numbers until it is easy to write them, including the place values of each digit in their numerals?

Then have them tell you what their own large numbers represent that is of personal interest to them —like how much money their dad makes? Or how many miles to California? Or how many houses in their home town? Or how many stars in heavens above? Or how many leaves are on the great oak tree outside?

The principle that a teacher – any teacher of any subject — has the right, the duty and the mission to encourage and assist her students to generate and develop their own ideas about any subject they are studying (once they have mastered the book’s basics on that subject) is hardly a revolutionary concept.

In fact, it is being done right this minute in just about every school in the land with just about every subject —except math!

The intentional application of Step Two of OSOM, Problem Creation in Mathematics, to the math classroom at any level of math is a natural evolution in teaching the subject, an evolutionary step which recognizes that a student studying math – whether that math be arithmetic or calculus – will learn more and be more able to use math in his life if he is encouraged to think for himself.

A SPECIAL NOTE TO READERS:

To make this website version of The Other Side of Math more accessible to the greatest number of readers, I intended to limit its length to a maximum of 200 print pages. However, as I continued researching, writing and illustrating, it quickly passed the 200-page mark and kept on climbing, soon approaching 300 pages. While 300 pages is an appropriate size for the (future) hard-copy version of OSOM, it’s exceptionally long for a single website article. Therefore, to condense OSOM, I had to delete content. My criterion was, “What will most readers not need?” On that basis, I chose to remove Parts 9-A, 9-B, and 9-C.

PART 9-A, PART 9-B, AND PART 9-C.

These three parts contain detailed programs devoted to implementing the OSOM program into tutoring practices, homes schools, private and public schools, colleges, universities, and graduate schools.

If you are planning to implement the ideas and practices of OSOM and Math Creativity into a school or tutoring center of any kind, you can contact me via my math educator’s website (MathCreativity.com) or my artist’s website (BruceSilton.com). Please describe your plans (include such data as the school you are considering implementing OSOM into, when you intend to start implementation, if you would like my assistance, etc.) I will then email Parts 9-A, 9-B, and 9-C to you. There is no charge.