∞ LITERACY, MATHEMATICS,

AND CREATIVITY ∞

An Essay for 2016

by Bruce Silton

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As an educator, I neither think nor act in a vacuum. After nearly seventeen years of immersion in the educational world of Clearwater Academy International, I barely recognize the innocent adult who walked in the front door of the school in January of 2000 seeking employment as a tutor. In the years following that time, the ideas and practices of the school’s remarkable staff, faculty, curriculum and students have fashioned a new and more capable me. The names of those who contributed significantly to the new Bruce Silton forms a very long list indeed. I cannot name all of you, but you know who you are and the impact you have had on my thoughts and actions concerning education and children. I thank you — each of you — for helping me become a man who helps children.

The following outstanding individuals deserve a special thank you.

Rhonda Zombory, Clearwater Academy’s Curriculum Director, is the author of a comprehensive (69 page) Algebra One Glossary that was my trusted companion while I struggled to learn the basics of Algebra at the age of 67. It is likely I would have failed to make the grade without it. Also, her essays, instructions and definitions that form the core of CAI’s reading and writing program got me started in precisely the right direction.

Jim Zwers, the Executive Director of Clearwater Academy International, who introduced me to two powerful fundamentals: first, his concept of a “goals-oriented education”: the firm principle that the education a person receives must be oriented to that person’s own goals; and second, his “300 % responsibility” principle – the ethical idea that responsibility for a student’s success lies 100% with the school, 100% with the parents, and 100% with the students themselves. My consistent application of these two practical concepts has carried me safely through adventures and misadventures too numerous to count.

Bonnie Paull, Professor Emeritus of English, my dearest friend and fellow writer, who practices the saintly arts of listening, understanding and cooking. In her presence — because she listens so well and with such a depth of understanding — I am able to clarify, formulate and enhance my ideas about education.

Paige Perkins, minister, teacher, curriculum developer and total friend for 48 years, who works relentlessly to develop reading and writing curriculum that will enable her students to achieve true literacy.

Marlene Glickman, who, by the example of her own life, has set the highest standard of artistic communication.

John Saxon Jr., West Point graduate, engineer, test pilot, mathematician, educator, author, and publisher whose Saxon series of math textbooks (from 4th grade Arithmetic through Algebra Two) opened my artist’s eyes, ears and mind to the music of mathematics, unlocking the door to a new life as a math educator.

Finally, L. Ron Hubbard’s study methods and philosophy of education have influenced and enhanced every aspect of my work with children.

Bruce Silton

Pinewood Village, Clearwater

November, 2016

Note: Naturally, as an author, I accept full responsibility for the ideas expressed in “Literacy, Mathematics and Creativity.” The concepts and practices described in this essay are, ultimately, my own and not necessarily those of my school, its faculty or curriculum.

FIRST WORDS

FIRST WORDS

As a tutor on the faculty of a top-notch, international private school, I have the privilege of teaching students from the time they start their formal education in kindergarten.

Day by week by month by year, their minds and bodies grow towards the sky — until that special day when I must tilt my head backwards and look up in order to talk to them.

The final moment comes in May of each year. Surrounded by colleagues, students, parents and guests, I am present in the auditorium of the Fort Harrison Hotel when our graduates, dressed in cap and gown, stand proudly on the stage, accept a diploma, eloquently express their thoughts, feelings and thanks for the education they have received and accept a round of well-earned applause.

Then, for a perfect ending (and a perfect beginning), they vanish into the working world or sail off to a near or distant university.

I wish them well on their journey through life.

MY INTENTION

MY INTENTION

My intention in this essay is, first, to fully define and describe “literacy” as it applies to the real world of the twenty-first century. Following that, I expand the concept of literacy to include subjects in addition to reading and writing, especially math literacy — or “numeracy”, as it is often called. Finally, I introduce the goal of “Creative Math Literacy” as an ideal and desirable product of education, along with a new teaching method – “Problem Creation in Mathematics” — to help students reach that desirable result.

TOWARDS A HIGHER STANDARD OF LITERACY

TOWARDS A HIGHER STANDARD OF LITERACY

In my school, it is the classroom teachers who oversee and guide a student’s education. Tutors support the teachers. To give my best to both teachers and students, I must look ahead. When I look, I see a sci-fi world coming down the pike at three times the speed of light. Some aspects of the future reveal the hand of a friendly magician while others seem the creations of malicious fairies — powerful computers that fit on a wrist, intelligent cars that drive themselves, Mars landings that underline the genius of Man, but also genetically-modified plants, animals and foods, spy drones available on-line for a few bucks, websites that divulge our deepest, darkest secrets and a strange (perhaps only strange to me at 73) landscape of human beings glued to smart phones – and some of these folks would rather text than actually communicate (eyeball-to-eyeball) with someone standing next to them.

In 2016, I realized that if we wish to remain genetically UN-modified people, if we want to rise above this planetary onslaught of brilliant, fascinating but potentially overwhelming computer/machine/robot technology, we must improve our concept of literacy.

For my own work as a teacher of children and young people, I wanted to answer this question:

“HOW LITERATE DOES AN INDIVIDUAL STUDENT NEED TO BE?”

THE BARE-BONES DEFINITION OF LITERACY

THE BARE-BONES DEFINITION OF LITERACY

The bare-bones, dictionary definition of literacy — “the ability to read and write” — is inadequate to encompass a concept and ability so central to the individual’s survival in the twenty-first century. Once upon a time, possessing merely “the ability to read and write” may have been good enough, but that simplicity is no longer true.

Happily, at least one dictionary (my all-time favorite, the Encarta Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language, Second Edition) goes beyond the stripped-down version, adding the idea of “competence.” The definition then becomes “the ability to read and write competently.” Much better! Heading in the right direction…

But still not quite good enough.

So, I set a higher standard for myself as a tutor: I evolved, polished and kept in mind (at least, most of the time,) a personal standard with which to judge the results of my labor: TRUE LITERACY.

Literacy, of course, has two faces: reading and writing, the receiving and giving of ideas via the written word.

TRUE LITERACY

TRUE LITERACY

True Literacy in Writing

In the challenging world of 2016, a truly-literate person must write well enough to communicate his own ideas easily, accurately and persuasively. This ability enables him to contribute to and influence positively the culture in which he lives. By writing, he can give others the knowledge and skills in his possession. By means of his own written words, he can change conditions for the better.

True Literacy in Reading

A truly-literate, twenty-first-century individual must read well enough to thoroughly and accurately grasp the ideas of others. By reading, he can receive and understand the goals, knowledge and skills possessed by his fellows. In this way, he can actively and safely participate in a swiftly changing and sometimes dangerous world.

GOALS AND LITERACY

GOALS AND LITERACY

Also in 2016, faced with an ever-challenging present and future for our students, I pushed my personal concept of literacy up yet another notch, reaching for an even higher standard than the one stated just above.

I now consider students truly literate only when they have the ability to read and write competently up to the level where they have the opportunity to achieve their own truest goals.

Does that young man or woman, on the verge of graduating high school (or technical school, college or graduate school, etc.), possess the reading-and-writing horsepower to reach his or her very own mountaintop?

IT IS THE INDIVIDUAL’S GOALS THAT SET THE LEVEL OF LITERACY REQUIRED BY THE INDIVIDUAL.

If we name and define what true literacy is and aim for that with each individual student, and let the students know that THAT IS THE STANDARD, the result will be more productive, contributing, happy, successful men and women who live in a world that is better because they are alive.

LITERACY IN OTHER SUBJECTS

LITERACY IN OTHER SUBJECTS

This year, I also defined for myself yet another kind of literacy: literacy in a particular subject or activity. This is what we mean when we say that someone is “computer literate.”

This second kind of literacy involves gaining sufficient knowledge and skills so that the individual can function competently or professionally in one or more specific subjects or areas of knowledge and activity.

Consider mathematics, the planetary language of quantities and shapes used by all the sciences. Using math skillfully, a man or woman can observe, state, and solve just about any problem involving quantities, numbers, shapes and sizes that arise in human activity. To function most effectively in this ultra-high-tech culture, each man or woman should possess a high degree of competence with mathematics.

As a math tutor, I had to answer the following question for myself:

“FOR ANY ONE INDIVIDUAL, HOW MUCH MATH IS ENOUGH MATH?”

WHAT IS MATH LITERACY?

WHAT IS MATH LITERACY?

The answer resides in the following definition of “math literacy.”

The minimum (minimum) level of “math literacy” consists in the individual’s ability to comprehend, read, write, and apply mathematics competently in his handling of our present culture (and the ever-approaching future) to a degree at least equal to the goals he has set for his lifetime. How much math will he need to reach his mountaintop?

A young woman who intends to save the lives of animals as a vet should master a definite level of math prior to graduating high school. Another student, whose eyes are set on, perhaps, the artistic life of a ballet dancer/choreographer or becoming an outdoor leader and mountain guide or a mechanic maintaining and repairing modern, computer-heavy cars, will each have a different math requirement to be math literate.

Naturally, in order to achieve that level of competence with mathematics, the individual would also need to be truly literate in reading and writing his own language as described above.

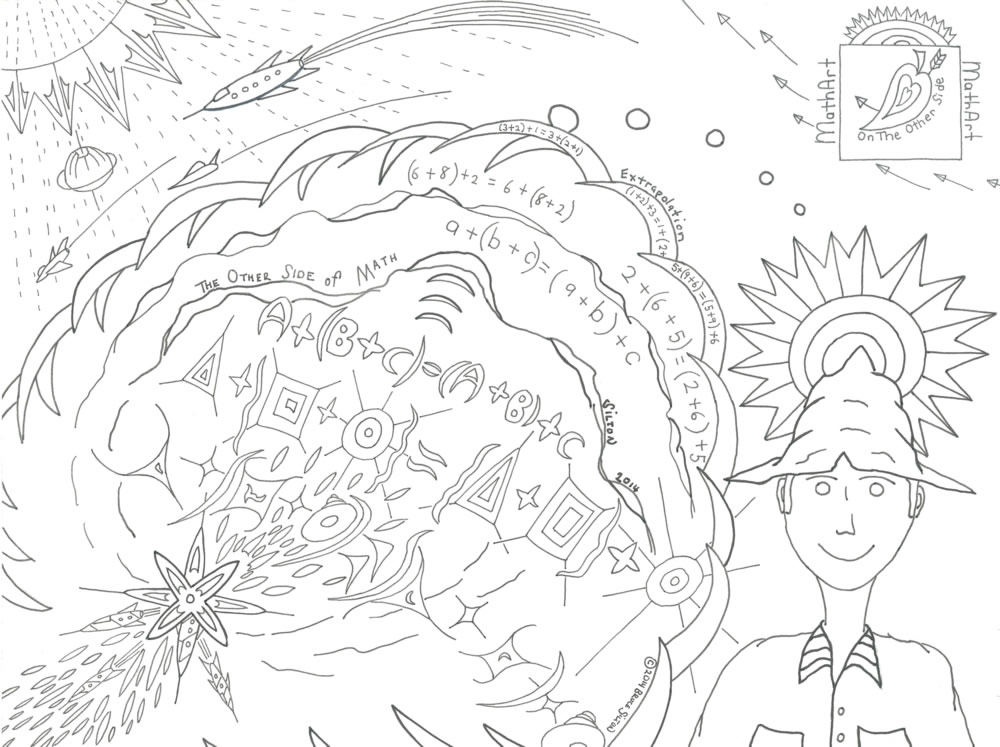

∞ THE OTHER SIDE OF MATH ∞

WORKING TO ACHIEVE

A HIGHER STATE OF MATH LITERACY

CREATIVE MATH LITERACY

CREATIVE MATH LITERACY

This section introduces the concept of “Creative Math Literacy.” It seems possible that I am naming, defining and describing a new kind of literacy. “New” often involves ideas that are off the well-walked path. As such, they are sometimes rejected hastily, without being granted the opportunity to BE. So, please, readers, push open the door to your personal universe. Thank you. Now hold that door open with one hand and read on with the other….

Because I am a professional artist as well as an educator, I have set an additional personal goal for our students: I intend to not only help individual students achieve math literacy (as defined above), but do so in way that develops each individual’s full and unique potential for creative thought and creative activity while using the language of math.

My goal definitely, specifically and particularly includes students adding back their own knowledge into the subject of mathematics itself — each of them contributing their wisdom to its development. I think of this as “Creative Math Literacy.”

This goal is not limited to those young people directly in my care or even to all those students studying at my school. My goal includes every young person everywhere on Earth!

Some might consider this purpose to be ridiculously large, an extravagant, unreal and unattainable luxury existing in thought only.

I do not think so. I do not consider an educated state of “Creative Math Literacy” to be extravagant, unreal or unattainable. True, it states a lofty ideal, but one that can be achieved. Regardless of barriers, it is worth achieving.

A critic might now say, “OK, BRUCE, SO YOU HAVE BIG THOUGHTS…BUT, COME ON, IS IT REALLY POSSIBLE?

Yes. And there’s an easy way to start: with PROBLEM CREATION IN MATHEMATICS.

“SAY WHAT, BRUCE? CREATING WHAT PROBLEMS WHERE?” questions the critic.

PROBLEM CREATION IN MATHEMATICS

PROBLEM CREATION IN MATHEMATICS

It is this simple: Each time a student masters a new topic in Arithmetic, Pre-Algebra, Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Pre-Calculus or Calculus, (and I mean, MASTERS that new topic, not “passes his test” or even “gets 100% on his exams”), and before he continues on to the next topic in his textbook, tell him to invent or create or make up a math problem of his very own directly on the topic just mastered.

His problem must be similar to those offered in his textbook, yet still be his very own. That means “created without referring to the book, computer, teacher, notes or friends or anything except his own mind and understanding.”

When he has done so, have him solve his just-created problem using the exact same solution procedure learned from his textbook. (This ensures he has actually understood his textbook’s presentation and not sailed off into a “dark mathematical unknown” caused by misunderstanding the principles and procedures delineated in his book.)

Finally, when he has solved his very own math problem, he must check his answer for accuracy – after all, there is no answer book for self-created problems; it is the problem-creator’s mind that provides the only answer book for self-created problems.

And all of this — problem creation, problem solution and problem checking —must be done with excellent handwriting that shows each and every step of the solution and checking process (no mental math allowed.)

If he has honestly and fully mastered that new math topic, his self-created problems will usually roll out onto paper like they were patiently waiting to be born into the physical universe.

I’ll be specific. At an elementary level, a second grade student who has just mastered the topic of “fact families” would (with his book closed and on his own) choose three numbers, such as 5, 7 and 12. Using only those three numbers, he would then write four different math facts — two addition facts and two subtraction facts:

![]()

The mere fact of choosing the right numbers and then successfully creating this series of four interrelated math problems and solving them on his own without the aid of teacher, book, notes, or parents, has raised him above the usual state of dependence upon teachers and books that is the fate of all too many math students.

Once the student has created his two addition and two subtraction facts, he would then (all on his own and with his book still closed) have to check the answers using the checking method taught by his second grade textbook or teacher.

Finally, he would have to demonstrate to the teacher that he understood the relationships between the numbers. For the two addition facts shown above, he would explain (using both words and sketches) that the order in which numbers are added does not change the sum.

This very same process is used consistently with every topic mastered in higher Arithmetic, Pre-Algebra, Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, Trigonometry, Pre-Calculus and Calculus. Topic by topic, as a final step in learning that topic, the student creates, solves and checks his own problems. This is the core of “Problem Creation in Mathematics”.

Naturally, sometimes it’s not quite so easy. Then the student might clench his (or her) teeth, or squint and bend closer to his desk, anxiously rolling a pencil across the wooden top, or making uncertain marks on a blank sheet while strange sounds emanate from his lips.

But, eventually, with or without coaxing, out it comes: his very own, newly- created problem formed with his own ideas of how many and how much, his own words and numbers, his symbols, his expressions, his equations, his points, lines, planes, flat and solid shapes.

Of course, if he has not mastered the topic for real, he will be very unlikely to create, solve and check a problem for that topic. When this happens (and it does), you simply return him to his textbook, clear up his misunderstandings and hone his skills in that same topic until he HAS mastered that topic for real! And then go back to the “create, solve, and check” a problem step.

A critic might now exclaim: “BIG DEAL, BRUCE, AND SO WHAT? WHY, IT’S ALMOST NOTHING! A MERE FACT FAMILY! SUCH A TINY CREATION! PHAW!”

IMAGINE THIS FUTURE

IMAGINE THIS FUTURE

Yes, I agree, each self-created problem, solved and checked is only a tiny creation — but a miracle nonetheless.

Why? Imagine this future: What if every time a math student of any age anywhere on earth — billions of them — mastered (MASTERED!) a topic in his textbook, he then created a similar math problem, solved that problem using his textbook’s procedure and then checked the answer, all three steps done on his own? And what if he continued creating, solving and checking similar math problems for that specific topic until it was easy – all on his own without referring to textbook (or other authority) and before tackling the next topic in his textbook? What might be the accumulated effect upon the individual of one or two thousand such creative certainties (the estimated total number of major math topics and skills that one student masters between 1st and 12th grades)?

AND WHAT MIGHT BE THE ACCUMULATED PLANETARY EFFECT OF THOSE ONE OR TWO THOUSAND INDIVIDUAL CREATIVE CERTAINTIES MULTIPLIED BY BILLIONS OF STUDENTS?

MATH MIRACLES, OF COURSE!

(Note: “Problem Creation in Mathematics” is Step Two of a six-step program, “The Other Side of Math”, I have developed to help students achieve Creative Math Literacy. “The Other Side of Math” includes four additional steps above Problem Creation.)

THE PURPOSE AND PRODUCT OF

THE PURPOSE AND PRODUCT OF

“PROBLEM CREATION IN MATHEMATICS”

How does Problem Creation in Mathematics work to develop the Creative Math Literacy of the individual?

The answer lies in the difference between problem solving in a school environment and solving problems in a real-life environment. In school, the problems are carefully designed and presented by a math teacher or book, and a well-trained teacher is present to help you understand the problem and its solution.

But in real life? The student, now no longer a student, now en route to achieving his goals, must see, state and solve his own problems. Outside of school, there are usually no teachers handy to help you see your problems. And no teachers at hand to tell you how to state the problem correctly (whether stated mentally or written down). And certainly few books with ready answers to your own math problems.

Real life activities can be fast and messy, sometimes difficult and occasionally chaotic. Therefore, if one wishes to survive and at a high level, if one wishes to make sense of the immense variety of personal, family, professional, social and physical universe situations that one is required to handle competently, the student (who will soon become a grownup) must take every major math topic learned in school and drill problem-creating, problem-solving and answer-checking skills with that topic until he has achieved a high level of competence without referring to his book or teacher.

The result is a higher level of Creative Math Literacy than can be achieved by simply solving a math book’s problems, no matter how excellent those textbook problems may be.

LAST WORDS

LAST WORDS

Throughout this year (2016), in an effort to improve the results of my work as a tutor, I re-examined the fundamental ideas I was operating with. Amongst those fundamentals, I found a one-dimensional idea — the idea that literacy was simply the ability to read and write. That notion was replaced by a better idea: the notion of literacy as a series of dramatically varying levels of competence when giving and receiving communication via the written word.

With that improved understanding, another door opened. There stood “literacy” in the three-dimensional sense, as a series of “literacies” forming sort of a “scale” going both up (more literate) and down (less literate) and across – literate or illiterate in varying degrees in a variety of subjects.

In addition to reading and writing, the most important of these “subject literacies” is mathematics, which, I was happy to find, fits in well with my own interest in developing Creative Math Literacy in students of all ages.

The ideas and practices contained in this essay on literacy, mathematics and creativity enable me to view my students with greater clarity as regards the academic requirements for their future happiness and success. True literacy, honestly and fully attained by an individual – in reading, writing and mathematics (all three) – gives that person a much better chance for a successful life.

Perhaps my ideas on literacy, mathematics and creativity are useful to you, as an educator or parent? Perhaps you are working professionally in this or a similar area and have ideas of your own you could share with me? I look forward to hearing from you.

the end

Copyright © 2016, 2017 Bruce Silton

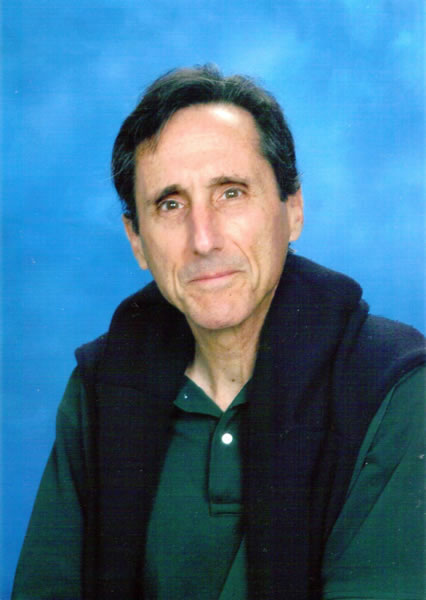

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bruce Silton is a tutor at Clearwater Academy International, a preschool –12th grade private school in Clearwater, Florida. Since March of 2000, he has delivered approximately 17,000 tutoring sessions to students of all ages. Some 10,000 of those tutoring sessions have been devoted to helping students overcome difficulties learning math.

Bruce Silton is a tutor at Clearwater Academy International, a preschool –12th grade private school in Clearwater, Florida. Since March of 2000, he has delivered approximately 17,000 tutoring sessions to students of all ages. Some 10,000 of those tutoring sessions have been devoted to helping students overcome difficulties learning math.

A six-step program to develop “Creative Math Literacy” (which includes “Problem Creation in Mathematics” as the second step), is described in detail in his book, The Other Side of Math. It will be published sometime in 2018. A condensed version of The Other Side of Math can be found on www.MathCreativity.com.

The author can be reached using the contact page of his math educator’s website, www.MathCreativity.com, or his artist/designer’s website: www.BruceSilton.com